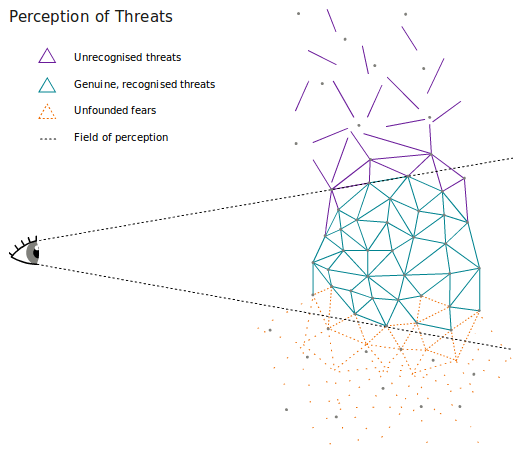

Developing a useful security strategy is heavily dependent on our perception – we need to be able to identify and analyse threats in order to implement ways of avoiding or reducing them. But we all perceive the world around us differently based on our circumstances, experiences and many other factors. As a result, our perception can sometimes be hindered: threats which may be evident to some people may go unrecognised by others; similarly, we also need to be able to tell the difference between threats which are genuinely possible and those which we falsely perceive, called 'unfounded fears'. It's a good idea to become familiar with factors that condition our perceptions of threat, and consider ways that we can take these into account in our security planning.

Intuition and survival responses

Everyone has natural protection mechanisms which have developed through our evolution – many of these are operating even though we are not aware of them. A common example is intuition: when our intuition is signalling untrustworthiness or danger, it is often because we have picked up multiple, subtle indicators which alone do not identify a particular threat, but taken together strongly suggest that we may be in danger. This intuition often produces anxiety which leads us to either take direct action to protect ourselves, or seek out more information to establish whether we are in danger.

Depending on what we find out, this anxiety might develop into fear, triggering one or more survival responses. These survival responses – common examples include 'freezing', 'flight', posturing or fighting, among others -- often kick in when we feel we are in immediate danger, and much of our behaviour then becomes automatic, and more difficult to control. We become quicker, stronger, and more focused. As a result, these survival strategies are extremely effective in many circumstances. However, this is not always the case: it's important to recognise that we do not always have control over our reactions to immediate danger, and should be careful in assigning blame to ourselves or others for how we react in these cases.

The digital space

Even though you might only be beginning to develop your own organised approach to security, it is good to know that your natural survival mechanisms are already hard at work to keep you safe. However, there are times when our instincts are not trustworthy and we should exercise caution. The digital space – our computers, phones and other devices, and the systems that help them communicate – is often woven within the fabric of our offline lives but our abilities to detect digital threats are far less developed than our abilities to detect physical threats. Surveillance and harassment over the internet and mobile phones is often secretive and it can be difficult to perceive, prevent or pursue justice for it. We often fail to recognise these threats, or conversely we perceive threats which may not actually be there.

In order to better perceive and plan for these threats it is important to get a deeper understanding of how the technology we use daily works. Since human rights defenders are subjected to ever more sophisticated means of electronic surveillance and increasingly depend on digital tools to do their work, we need to recognise that our information is a valuable asset and grow our understanding of it: how and where it is stored, and who may have access to it. With this knowledge, we can then take action to protect our information and communication.

Trauma, stress and fatigue

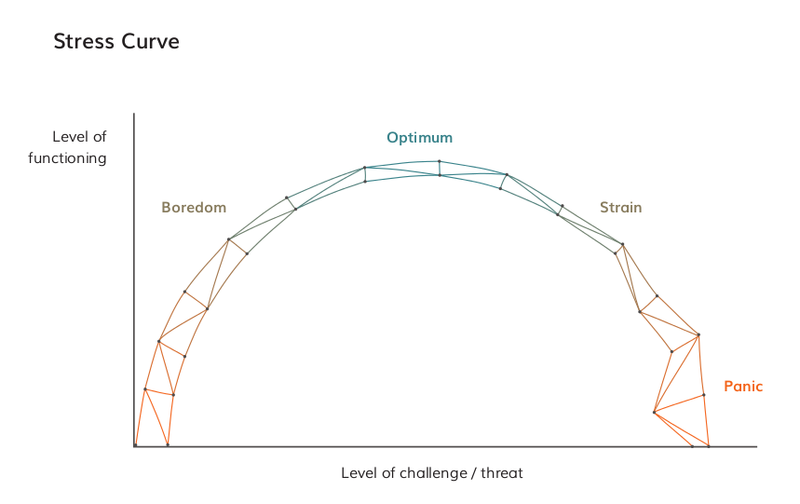

Finally trauma, stress and fatigue can all impact upon our perception and therefore on our ability to identify and respond to threats. If we have experienced very disturbing or traumatic events, our response to indicators of danger may be distorted. On the one hand, it can result in our overreacting – seeing danger where none exists; on the other hand, mental exhaustion as a result of trauma may mean we stop paying attention to such details and fail to identify real and present dangers.

The same goes for stress and fatigue, which can also affect our ability to realistically gauge the level of threat in our environment. Making a concerted effort to keep our work/life balance in check and being realistic about the amount of work we take on and the number of commitments we make can help us avoid becoming overwhelmed.

A certain amount of stress in our lives is normal – even healthy – and keeps us from becoming bored or depressed. But even though we can cope with higher levels stress for short periods of time, we become overwhelmed if such high levels persist. This can result in our becoming panicked, eventually despondent and possibly depressed.

As a result, developing a culture (both individually and as a group, organisation or movement) of stress management and self-care is fundamental to a holistic approach to security. Not only will this help to prevent threats brought about through long term exposure to stress and fatigue, but it will greatly aid critical thinking about security in general.

The following two exercises provide an opportunity to reflect on our experiences, including how we have perceived and reacted to threats in the past and how traumatic events may continue to affect our perceptions of danger in the present. Developing a better awareness of these makes it easier to establish tactics for keeping our perception 'in check' in the future, which is a key component of our security plan and process.